Exploring the History of Toronto’s Big Waterfront Dreams

What is it about our waterfront that draws us in? What inspires the dreams, plans, schemes and proposals that range from the utilitarian to the awe-inspiring? (Image courtesy of Diller Scofidio + Renfro and architectsAlliance, from their 2010 design ideas proposal for the Gardiner Expressway.)

POSTED: AUGUST 27, 2014

BY: CHRISTOPHER MCKINNON

Our city, the city of Toronto, has had its share of big dreams for the water’s edge. We got to look through a number of them assembling this exhibition, Dreaming Big, which is on now until October 11th at the Toronto Reference Library’s TD Canada Trust Gallery.

Looking back at Toronto’s history, from the days of Muddy York to the gleaming glass metropolis of today, there have been plenty of plans – big and small – for Toronto’s waterfront. From parkland to housing to industry and back again, the people of Toronto have proposed and debated many ideas of what our waterfront should be. One of the first to catch our attention – John G. Howard’s plan – (sketched in 1852) was a plan for a series of parks and public spaces that would run along the shoreline from Bathurst Street to York Street.

“Sketch of a Design for Laying Out the North Shore of the Toronto Harbour in Pleasure Drives, Walks and Shrubbery for the Recreation of the Citizens” – John G. Howard, 1852

“Sketch of a Design for Laying Out the North Shore of the Toronto Harbour in Pleasure Drives, Walks and Shrubbery for the Recreation of the Citizens” – John G. Howard, 1852

The story we’ve often been told, the one that has cemented itself in our minds as part of the “history” of Toronto’s waterfront, was one of a waterfront that always and only industrial. From the earliest days, we thought, the citizens had known only industry, only commerce. But, quite clearly, this is wrong. In fact, Torontonians have always considered the water a place for leisure and recreation (though perhaps our notions of what constitutes leisure and recreation have changed), if also a place for industry and commerce. The notion that these things are necessarily in a kind of conflict is a false one. Our waterfront can be – always has been, always will be – both. See then, from just one year later, the plans for the route of the proposed railway.

Proposal for the Grand Truck Railway and Lands Surrounding from 1853.

Proposal for the Grand Truck Railway and Lands Surrounding from 1853.

The two plans, one for a massive park and another for a railway, seem in conflict and yet they aren’t necessarily. They represent two sides of a dialogue that has been happening for well over 150 years. The nature and spirit of this kind of dialogue is very much in evidence in the next item, a broadside from roughly the same time period.

The headline reads: “Toronto, Simcoe, & Huron Railroad. Questions Which Ought to be Answered by the Railroad Committee to the Satisfaction of the Citizens of Toronto, Before They Record Their Votes.” And then it goes on to list fourteen important questions – and they are important – about how the route was determined, which alternatives have been considered, how will it be financed, who will pay the on-going operating costs, and so on. (Interestingly, and perhaps an early precursor to the way we debate today, we note that each of those questions is just about the right length for a tweet.) But, more importantly, these are the types of questions we still ask ourselves today when trying to decide on big investments in infrastructure. Whether it’s the Gardiner Expressway, building a new subway, or deciding if the Island Airport should be expanded – as a city we tackle these very same issues in the course of our public debates.

Two Visions, One Debate

As we assembled Dreaming Big, we debated too, out of the vast trove of the Toronto Public Library’s special collections, which items to include and which would have to be left out. Which items best illustrate this on-going dialogue? What items from the archives best relate to the designs and images from Waterfront Toronto’s collection? How did they interact to tell a story of our evolving waterfront plans?

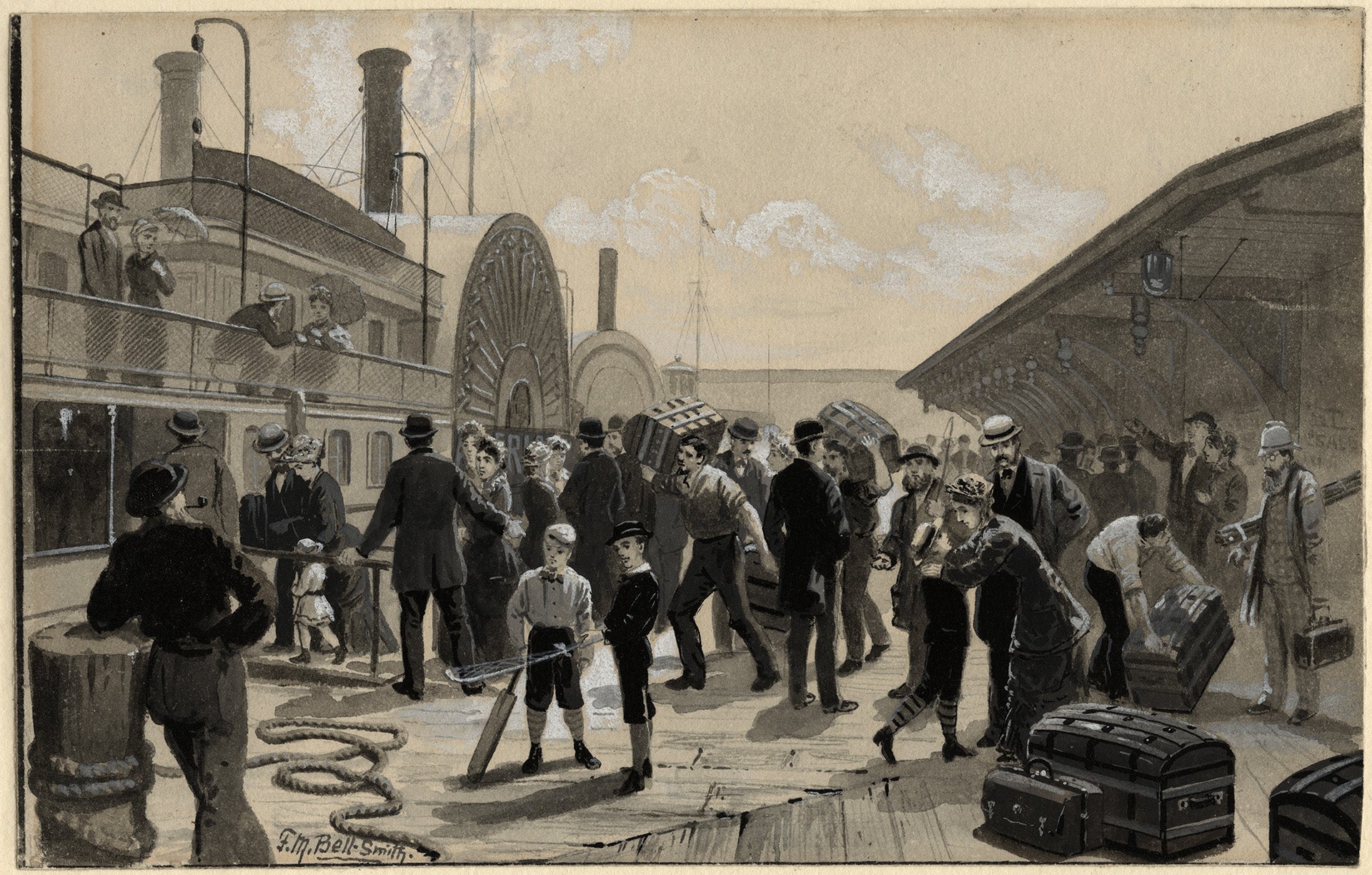

We quickly found that the late-19th and early-20th century photographs and paintings told an interesting story about the area that we at Waterfront Toronto often call the “Central Waterfront” (for most Torontonians, it’s just “The Waterfront”), that area from just west of Yonge Street to just west of Bathurst Street along Queens Quay. Back then, it was the part of the water’s edge that was most built out with piers and docks, where steamer ships packed up people and goods to move them along the waterways. From many perspectives, it was a site that incorporated both leisure and commerce nearly from day one.

In this painting by F. M. Bell-Smith from the late 1880s, the wharf at the foot of Yonge Street is alive with activity.

In this painting by F. M. Bell-Smith from the late 1880s, the wharf at the foot of Yonge Street is alive with activity.

Along the Yonge Street Wharf, F. M. Bell-Smith's painting shows travelers loading their trunks for a voyage. Two young boys stand nearby with their cricket bat and golf club and in the far right of the painting is a man who may be a photographer, carrying his tripod and camera case. A man with a fishing rod is also visible in the crowd. The public spaces in early photos and paintings like this one are in many ways reminiscent of the designs for the new Queens Quay. Bustling, lively, public spaces that touch the water’s edge. A mixture of activity that balances leisure and recreation with commerce.

The design for the new Queens Quay restores and reinvigorates the waterfront’s history of being a busy, bustling place for people. A widened pedestrian promenade, boardwalks and “wavedecks” create places for people to explore, to sit and talk, to play.

The more we delved into the archives, the more we could see patterns emerging. Industrial areas seemed always to be photographed or painted in such a way as to highlight the beauty of the views, despite the industrial backdrop of our working port. When we put those images side by side with the drawings for the new Port Lands, by Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates, we could see a through line – industrial areas that seemed alive with nature – urban, industrial and natural all at once.

The city skyline and the natural beauty of Toronto’s harbour are celebrated in both this lithograph of a drawing by C. Gascard from the 1870s (above) and this artist’s rendering from 2013 of Michael Van Valkenburgh and Associates proposal to create a naturalized river mouth of the Don River (below).

Perhaps some of the most interesting “dreams” that we considered in assembling this exhibition were related to Toronto’s stormy love affair with the Gardiner Expressway. From the late 1950s, when construction first started, to the grand opening in 1960, Torontonians debated the highway furiously. Newspaper headlines rang with optimism and pessimism – and ultimately Metro Chairman Frederick Gardiner won the day (and the highway bears his name in honour of this). Though many a Toronto urbanist in the 21st century has bemoaned the expressway and how it cuts the city off from the lake, its continued existence and the question of its future are very much part of our city’s developing identity.

Whether you love it or hate it, the form and location of the Gardiner Expressway defines Toronto’s waterfront. Early proposals for the expressway called for the relocation of Historic Fort York, in order to improve the expressway’s alignment. Prominent Torontonians rallied around the historic site and blocked the plan, but the debate raged on and in many ways it still does. (Illustration from The Toronto Star, October 4, 1958, via Torontoist.)

With the Gardiner fast reaching the end of its lifespan, an aging piece of infrastructure from another era, in 2010 Waterfront Toronto sought design ideas from some of the world’s leading design firms. It was an effort to transform the debate and help Torontonians completely rethink the highway and the lands it sits upon. Six world-renowned firms offered their best and brightest ideas for removing, refurbishing or improving the expressway and reconnecting the city to the waterfront. These bold visions were a challenge to Toronto’s usually staid approach to building large pieces of public infrastructure, daring us to dream bigger than we ever had before.

Toronto’s own KPMB Architects, led by renowned architect Bruce Kuwabara, contributed this mega-proposal to the 2010 call – a massive redevelopment of the Gardiner Expressway with a plazas and raised park spaces connecting a series of angled office buildings and cultural spaces.

The result was a set of compelling city-building ideas that have infused our thinking about this perennial Toronto question: “What to do with the Gardiner Expressway?” That question and the answers supplied have helped to reshape the debate. Many of the ideas suggested have become incorporated into the plans both for the future of the Gardiner or adapted for use elsewhere in the city, and, of all the sections of Dreaming Big, this is surely one of the most compelling parts of the exhibition.

Over the course of two centuries, there have been many visions created for our water’s edge. In all of them, and certainly in those that have come to fruition, we see a constant interplay between industry and leisure. Some proposals were never realized, though the ideas and the public debate they stirred linger in today’s discussions. At the core of this exhibition is the notion that we can see these ideas emerge again and again – ideas and principles that demonstrate our collective passion for this socially, culturally and economically vital place. The waterfront always has been and ever will be our city’s greatest asset. And that is why we should never fail to dream big.

“Sketch of a Design for Laying Out the North Shore of the Toronto Harbour in Pleasure Drives, Walks and Shrubbery for the Recreation of the Citizens” – John G. Howard, 1852

“Sketch of a Design for Laying Out the North Shore of the Toronto Harbour in Pleasure Drives, Walks and Shrubbery for the Recreation of the Citizens” – John G. Howard, 1852 Proposal for the Grand Truck Railway and Lands Surrounding from 1853.

Proposal for the Grand Truck Railway and Lands Surrounding from 1853.