Get to know Ryan Rice, Waterfront Toronto's Indigenous Public Art Curator

Earlier this year Ryan Rice was selected to lead two site-specific public art calls for the West Don Lands, one to be located at the King/Queen/River Triangle and another at the future Indigenous Hub on Cherry Street.

POSTED: JUNE 9, 2021

BY: RYAN RICE

In January 2021 Waterfront Toronto announced the selection of Ryan Rice as our Indigenous Public Art curator following an open call to First Nations, Métis or Inuit curators with strong ties to the Greater Toronto Area (GTA). Ryan has extensive experience in the museum and art gallery sector and has worked at various centres including Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada’s Indigenous Art Centre, Carleton University Art Gallery, and the Museum of Contemporary Native Arts in Santa Fe.

To better understand Ryan’s curatorial practice and the goals for the prospective public art calls he is piloting, we sat down (virtually) for a conversation. Here’s what we learned:

How did you first become involved in public art?

Waterfront Toronto’s projects – Anishnawbe Health Toronto’s (AHT) Indigenous Hub and the King/Queen/River Triangle – are my first formal ventures in establishing permanent site-specific public art. However, I have been expanding my curatorial practice from the confines of the “white cube” over many years.

I have supported outdoor public facing art projects during my tenure as Chief Curator at MoCNA (Museum of Contemporary Native Arts, Santa Fe, New Mexico) by shifting exhibition opportunities outside of its gallery walls and utilizing the museum’s downtown exterior spaces, art park and courtyards. Framed as ephemeral interventions and rotating exhibitions, I commissioned murals and curated site-specific works to bring further attention to the dynamism and diversity of contemporary Indigenous art in contrast to the city of Santa Fe’s contrived and presumptuous aesthetics. Some of the artists participating in those projects included Nani Chacon, Anna Tsoularahkis, Will Wilson, Postcommodity, Frank Buffalo Hyde and Reko Rennie.

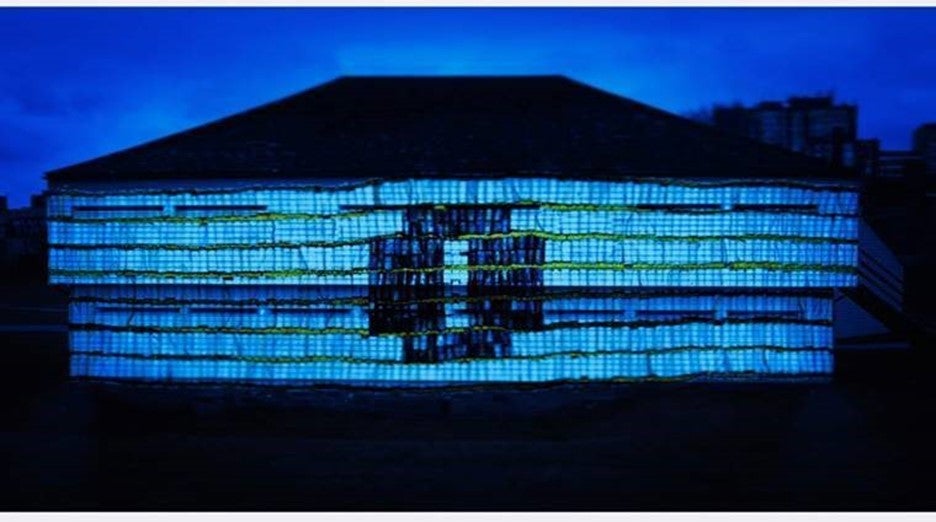

Rendering of Listen to the Land, Placeholders Collective 2019.

As an independent curator, I recently curated Listen to the Land with the ad hoc Placeholders Collective (Logan MacDonald, Jason Baerg, Vanessa Dion Fletcher and Aylan Couchie) at Fort York National Historic Site for Nuit Blanche 2019.

In my home community of Kahnawake, Quebec, I curated The Atsa’kta Project: At the Water’s Edge, whereby I commissioned artists Sondra Cross and Skawennati to create placekeeping signage signifying the community’s relationship to its namesake, by the rapids, to identify and observe the 60+ year disruption affected by the construction of the St. Lawrence Seaway. In 2007, I co-curated the public-facing project The Requickening Project as a collateral event on the occasion of the Venice Biennale in Italy. The project featured artists Lori Blondeau and Shelley Niro.

Can you describe your work so far with Waterfront Toronto?

Since the beginning of 2021, I’ve been collaborating with Waterfront Toronto’s public art program manager, Chloe Catan, to coordinate the Requests for Qualifications (open calls) that will support the public art opportunities identified for the two sites. In reviewing these opportunities, I’ve advanced my research to address the two locations framed within the West Don lands, historically and contemporarily, and their relationality to place and community within the urban landscape. Since I live near the area, I visit both sites consistently to understand how they are physically activated, traversed, and/or engaged by the public and to witness their transformations over the seasons. I’ve also engaged in a number of online community consultations, meetings and public engagements for other public spaces being renewed in Toronto to get a sense of feedback offered by local participants.

Additionally, I had to familiarize myself with the range of services critical to urban planning and development, which is significantly different than working within art and culture infrastructure and gallery walls. Mapping, envisioning and recognizing the distinct characteristics and constraints we need to address and work around for the two sites have been critical steps in supporting a range of options for the future public art prospects. I am also reviewing procurement processes and best practices to ensure these targeted opportunities for Indigenous artists will be experienced without barriers.

The triangular parcel of land at the junction of King, Queen and River Streets is one of the spaces that will feature a new permanent public art installation.

Why are these two sites important for Indigenous placemaking and placekeeping? How do you define placemaking and placekeeping?

“Placemaking and placekeeping” are guiding principles used to frame and reclaim meaningful relationships to place and the natural world that can bridge what was historically severed by a city’s evolving infrastructure and restored though Indigenous influence, visibility and representation in the public realm. These practices advance Indigenous values and can increase social empathy and cultural knowledge; expand the timeline of a city’s or site’s history beyond a settler colonial framing; build healthy and diverse relationships; and offer an influential sense of belonging. Such gestures affect the spaces one occupies (living, working and playing) through a form of reflective accountability that lends to developing meaningful relationships to home.

Placemaking and placekeeping efforts are critical to the future of restoring an Indigenous presence on the land and waters in and around Toronto. These aspirational and concrete actions have the capacity to support the renaturalization efforts taking place at the Don River Mouth and waterfront through a symbolic re-territorialization of place that will recognize the original owners’ and custodians’ sovereignty specific to the land acknowledgments offered in Toronto. Rekindling relationships to the land within the city will reorient original cultures and languages to place. This will also address the responsibilities of advancing a sustainable future through stewardship, which is outlined in the traditional (original) instructions reiterated through philosophies embedded in the Dish With One Spoon treaty.

What is your vision for the art pieces you’re curating at the King/Queen/River triangle and Anishnawbe Health Toronto’s Indigenous Hub?

In my role as Indigenous Public Art Curator, I conceived a curatorial premise to support open calls for the two projects that will encourage and inspire an Indigenous artist or artist team to map, build and develop their creative conceptions. I composed a narrative based on a multitude of factors that were drawn and align well with both the West Don Lands recognition of its diversity and Anishnawbe Health Toronto’s determination in building a healthy and thriving community that will be strengthened by introducing a unique highly visible and conceptual art work fostering relationship to community and place.

The future public art works can be imagined together or separate, yet the vision or possibilities of their presence is to address and frame Indigenous placemaking and placekeeping distinctly within the Don River’s landscape. These works can acknowledge the layers of histories embedded in place, critical custodial relationships and the future of urban Indigeneity. The curatorial objectives offer further tangible intentions for the future public art work to attend to, and can encompass physical, social, emotional and cognitive, as well as respectful sensibilities to community and diversity, infrastructure and design.