Both Beautiful and Functional: Toronto’s Next-Generation Stormwater Infrastructure

A new stormwater management system will serve the neighbourhoods in East Bayfront, the West Don Lands and future communities north of the Keating Channel.

POSTED: FEBRUARY 18, 2015

BY: CHRISTOPHER MCKINNON

What happens when it rains in Toronto? When it rains a lot – or when snow melts – any water that doesn’t get absorbed into the ground is known as stormwater runoff. As it flows along the city’s hard, paved surfaces it can collect grease, garbage, bacteria and plenty of other pollutants before finding its way into a storm sewer. Stormwater runoff is one of the leading sources of pollution in our lakes, streams and rivers. Heavy rainfall or a large snowmelt can overwhelm the sewer system, causing damaging floods – as Torontonians learned firsthand in the summer of 2013 – and dumping untreated stormwater into Lake Ontario. Of all the projects that Waterfront Toronto is working on, stormwater management and flood protection are two of the most important things we’re doing to help prepare our city for the future.

Why manage and treat stormwater?

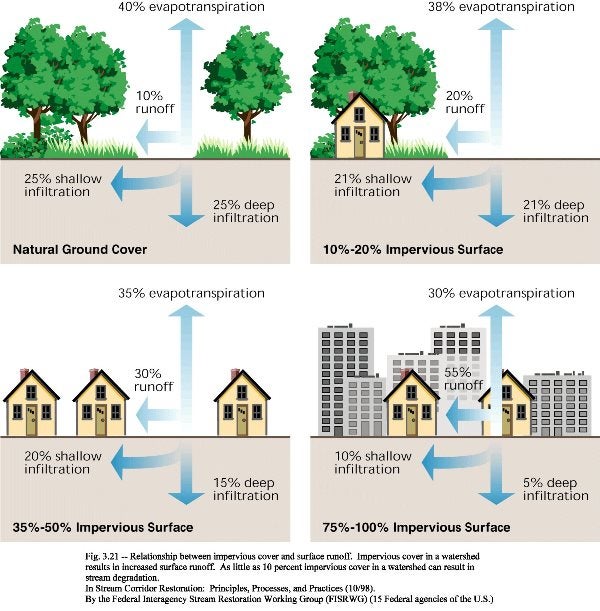

In a rural setting, rain and melting snow are usually nothing to worry about. They’re easily absorbed into the ground where soil, sand, gravel and plant material act as a natural filter for the water. In highly urbanized areas, like Toronto, the extensive paving and hard surfaces prevent the water from being absorbed, producing more runoff.

These four images show how runoff changes as an area becomes more developed and the amount of hard surface increases. (Source: The USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service)

With a growing population and increasingly frequent extreme weather, the City of Toronto’s sewer system – much of it designed and built between 50 and 80 years ago – is straining to meet today’s demands. Building new stormwater management systems is a pressing need for our new waterfront communities. The goal is to safely guide runoff, prevent flooding and ensure that any pollutants in the water are removed before being discharged into Lake Ontario. This helps protect the natural health of the lake, the plants and animals that thrive in it, our city’s source of drinking water, and the place where many Torontonians enjoy swimming, sailing and sport fishing.

Stormwater management can be beautiful

The first step in any stormwater management plan is to reduce stormwater runoff in the first place. Corktown Common is a great example of this principle in action. Many of the park’s features – rolling grassy hills, dense vegetation, the marsh – have been designed to slow runoff and allow water to stay where it falls, rather than running into the Don River. All of the park’s stormwater is sterilized using ultraviolet light and stored in underground tanks below the central lawn. The treated water is then used for irrigation and park maintenance, minimizing the park’s reliance on potable water from Toronto’s water treatment system.

Parks like Corktown Common can act as stormwater infrastructure. In this case, the parks landscaping and “soft features” help keep rain and snow melt where they fall, slowing and reducing runoff. Stormwater is disinfected with UV light and stored underground so that it can be used for irrigation and park maintenance. (Image credit: Dundee Kilmer)

To help manage the rest of the stormwater that falls outside of our parks and green spaces, we’re constructing an extensive stormwater management system that will serve East Bayfront, the West Don Lands and future communities north of the Keating Channel. We’re using an integrated design approach to build a beautiful and sustainable system that will serve Toronto well into the future, with capacity for future growth built in.

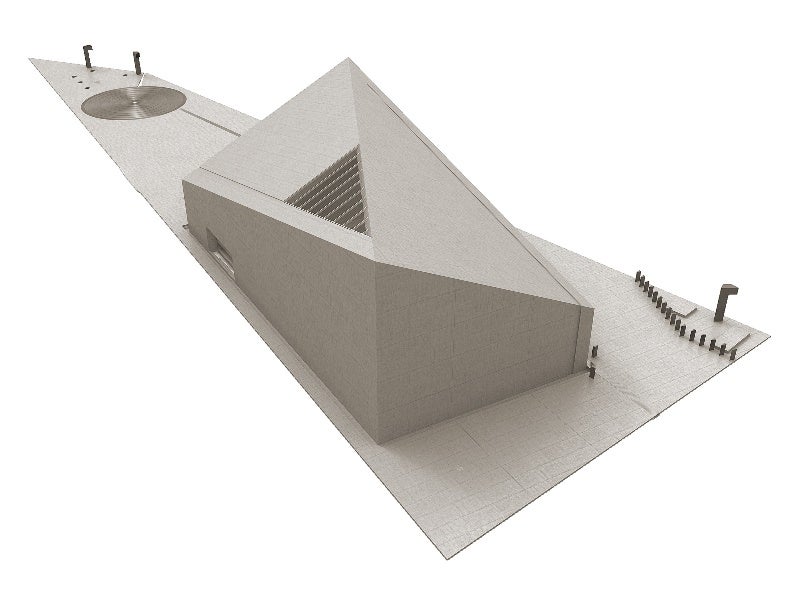

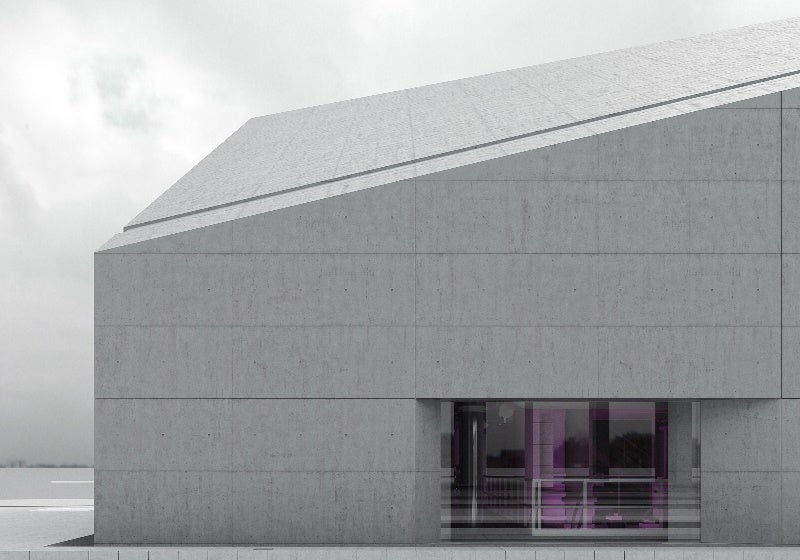

The design for this stormwater treatment facility is simple and elegant, embellished with rain channels that convey water from the building’s roof into a stormwater shaft below.

This stormwater treatment system will use a three-step treatment process. An oil and grit separator will remove sediment, debris and oil. Next, the water will be clarified as fine suspended solids are removed through a process known as “ballasted flocculation”. This process allows the system to make highly-efficient use of space and is more economical when compared to constructing traditional sediment ponds or tanks on contaminated sites. Finally, the water is disinfected using ultraviolet (UV) light before being released into the Keating Channel.

In keeping with Waterfront Toronto’s commitment to design excellence, the stormwater facility will be a landmark structure at the northeast corner of Lake Shore Boulevard and Cherry Street. The architecture team, gh3 and R.V. Anderson Associates, have created a simple and elegant form, embellished with etchings that will act as rain channels that run down the building’s roof and walls into the stormwater shaft below. A series of glazed openings in the building’s façade will reveal the inner workings of the system during the day and light up at night to become soft glowing features. The design was honoured with a 2011 Award of Excellence from Canadian Architect magazine.